Here’s why university faculties still have a diversity problem

Mar 01, 2023

7 mins

JB

Writer, translator and journalist

Universities in the United States have long talked about becoming places of diversity and inclusion. There has been some progress too. Between 2013 and 2020, for example, more than one-third of institutions improved access and completion rates among students from underrepresented communities. But one aspect that has seen little change is the make-up of faculty bodies. At current pace, it will take more than 1,000 years for those bodies to reflect the racial make-up of the country’s population. So why are US faculties so stubbornly pale? And what can be done about it?

The PhD pipeline

Securing a job as a faculty member is no easy thing. For starters, candidates have to have a very high level of education. In most fields of study, professors need to have a terminal degree, such as a PhD, to be able to teach at a university, according to Dr. Masica Jordan, assistant professor in the department of counseling at the University of Maryland’s Bowie State University.

Getting a PhD is a lengthy process. This throws up many issues along the way, starting already during K-12 with the school-to-prison pipeline and the dramatic differences in funding between predominantly white school districts and non-white ones. There are other issues as the student grows up. For example, pupils of color are less likely to graduate from high school and are less likely to enroll in college. They are also at a higher risk of dropping out of university. “There is a pipeline issue,” Jordan says.

For those who do stay in college, there are further complications they may not be aware of, such as the response their name might elicit, Jordan adds. “At most institutions, you need to produce X number of research publications. But there are biases with publications as to who gets accepted,” says Jordan, adding that she has had problems because of her first name. “I realized early on in my career that if I put Masica on my resumé, I was less likely to get a response. If I put M Jordan or M Williams [her maiden name], I would get calls back because they liked what was in my resumé.” When it comes to academia, however, the writer’s or researcher’s full name is required. “It’s not okay for me to put ‘Dr M Jordan’ on my application to peer-reviewed publications.”

Universities need to examine their systems and ask what they’re doing to diversify the pipeline of PhD students, according to Renu Sachdeva, an adjunct professor at the University of Houston and head of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) for North America at Talking Talent, which helps enterprises to build inclusive and equitable cultures. “Universities have a unique role in creating their own pipelines and in diversifying their workforce at the roots,” she says. “They are the ones that award PhDs.” To Sachdeva, colleges should be asking what they can do to diversify admissions and provide assistance to those from marginalized communities, such as making it easier for those who come up against financial barriers.

Diversifying the curriculum

Rigid institutional practices are often cited as an issue behind the lack of diversity in faculty bodies. Universities tend to be rooted in age-old traditions that are resistant to change, such as wearing gowns at graduation. Dr. Ziad Bentahar, an associate professor at Towson University in Maryland, says this rigidity extends to the curriculum too. “Underrepresented identities tend to specialize in underrepresented disciplines,” he says, “Therefore, when we prioritize the same old curriculum, it results in a group of professors that look like they’ve always done.”

Bentahar gives the example of what might happen after a hypothetical English professor, who specializes in Elizabethan drama, retires. When picking a new faculty member, the hiring committee has a choice: they can decide that Elizabethan drama is vital to the discipline and must be taught; or, they can take the opportunity to consider less studied fields, such as Black poetry. The latter, according to Bentahar, is likely to result in a hire that diversifies the faculty, while the former can perpetuate the problem.

“The faculty’s passion for Marlowe and Shakespeare can ultimately become a form of gatekeeping,” he says. He would like to see a fresh approach. “We can instead encourage the creation of new courses focusing on what underrepresented experts specialize in, rather than expect them to fit into a curriculum that was not designed with them in mind.”

Keeping staff matters too

Hiring isn’t the only hurdle, according to Dr. Katherine Rodela, associate dean of equity and inclusion for faculty and staff development at Washington State University — retention is important too. “There is too much focus on recruitment and not enough on reception and retention,” she says, adding that universities should look at their organizational cultures to ensure they are productive and safe places for people of color to work.

For many scholars of color, working within higher education can be a confusing minefield – but one that often has to be navigated alone. “At PWIs [predominantly white institutions], there is so much hidden curriculum around how you are supposed to be a professor [but], if you’re the first person in your family to go to college, you have to learn it all on your own,” Rodela says.

This resonates with Jordan, who says that at PWIs, she never had an academic mentor to provide guidance on how to get full tenure. “I didn’t even know this existed,” she says. When she started at an historically black university (HBCU), however, it was part of her orientation. She was told that she needed to connect with a full faculty member, model them and ask them for support. Jordan says this mentoring was “priceless” and ultimately led her to becoming tenured and receiving multiple awards. “I wouldn’t have known how to do this without someone telling me, ‘You need to do this’, ‘You need to be on this committee,’ ‘You need to be part of this’…” she says.

Navigating a difficult environment

Many scholars of color speak of giving additional service compared to their white counterparts. Bentahar again points to the curriculum saying that while a French professor and an Arabic professor may have the same job title, due to the prejudices and assumptions surrounding the Arab world, an Arabic teacher can face a heavier burden. He says this can be particularly troublesome when, due to curriculum design, the professor has to face this alone because there may only be one Arabic professor but 15 French professors. “When you are the only one, that is a heavy burden to bear and you’re less likely to succeed,” Bentahar says.

Rodela says it was only when she connected with a fellow Latina professor that she was able to articulate this concept of hidden labor in the form of extra mentoring, community outreach and requests from local families of color.

At the same time, she had to navigate microaggressions in the classroom involving students, as well as unprofessional comments made by senior colleagues about her appearance. This hostile environment can be difficult to remedy. Rodela says that, in higher education, there is a latent reluctance to report problematic behavior and racist incidents due to a fear of retaliation. “The aggressors are sometimes in the programs. They’re going to be in those meetings where they decide whether we get tenure or not,” she says, adding that, “Until we start reporting these incidents and using the structures that already exist in our institutions, we are going to keep having folks with problematic behaviors.”

Tenure is key when it comes to effecting change. “I’m now operating from a lens of privilege because of tenure,” Rodela says. “I now have the power to tell you how problematic my experience was.”

Rodela set up a mentoring group for new faculty members of color, which meets every week and provides a space to talk about these issues. Initially her white colleagues couldn’t understand why she had chosen to do this. “I just wanted this new faculty to have a different experience than I did while on tenure track,” she says.

Building communities

Fostering a sense of community is important because many scholars of color can find themselves excluded from the usual community-building that happens on campus. Bentahar explains, “If you have a department that looks alike, speaks with the same accent and has similar cultural references, its members tend to gravitate towards each other and form groups. But if you’re the faculty member who was hired to check the diversity box, you’re alone.” In academia, where mentoring and collaboration is key to getting ahead, this puts some at a disadvantage. “That faculty member is not playing by the same rules and yet is often held to higher standards,” Bentahar says.

This social exclusion can be hurtful. Jordan says that following a car accident, which forced her to wear a custom-made back brace and to use crutches, none of her colleagues at a PWI checked in on her. “There was no get-well card,” she says. “No one asked me if I was okay. That would have been a great acknowledgment that I was there.”

Her experience at a HBCU has been very different. After a sudden bereavement in her family, the chair of her department turned up at the funeral with a card signed by everyone in the department. “That says to me, you’ll be loyal to me, I’ll be here,” she says, adding “I can’t see myself anywhere else. I plan on retiring here.”

Bentahar suggests that cluster hires could address social exclusion. Rather than hiring one individual and placing them in a hostile environment with the aim of them single-handedly fixing diversity, why not bring in a few at once? “You can instead bring in a cohort that will create its own community, its own mentorship, its own collaboration,” he says.

Leadership is key

Rodela says universities also need to invest in their faculty members. As associate dean, Rodela has been working on how to compensate staff for providing equity-focused workshops. “It’s not about compensating for the burden, it’s about compensating for the lived experience and wisdom they’re going to bring. This knowledge is valuable,” she says.

Sachdeva agrees that leadership plays a vital role. “If you can’t see yourself represented in the leadership, it can make you question whether an organization is the right place for you,” she says. However, she acknowledges that diversifying leadership is a lengthy process, adding that even if an organization has a great DEI strategy in place, “diversifying doesn’t happen overnight.” By examining their systems, cultures and pipelines, however, educational institutions surely can accelerate the pace of change.

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: DEI

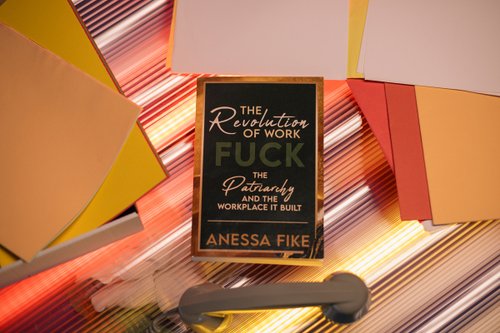

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

Dec 23, 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

Nov 06, 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

Oct 22, 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

Oct 14, 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

Sep 09, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs