Where are all the female software engineers?

Apr 25, 2023 - updated May 10, 2023

5 mins

Freelance translator and journalist

Although men are often seen as the stars of computer science, women have played significant roles in its development too. Ada Lovelace is recognized as the first female computer programmer, even though she was around in the 1840s before computers as we know them had been built. In the 1960s, Margaret Hamilton led the software engineering division of the instrumentation laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which developed the Apollo space program’s guidance systems for Nasa. Programmer Carol Shaw designed video games for Atari in the 1980s.

In 1984, women earned 37% of degrees in computer and information sciences in the US, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. By 2010, that number had more than halved, falling to just 17%. When it comes to employment, women held 30% of software engineering roles in the United States in 2010, though that number has since fallen to 22%. So why is this happening?

The stultifying effects of being in a male-dominated sector have been well documented, but that wasn’t a factor for Marlena Compton_, who spent 20 years as a software engineer. “I realized that even if the work conditions were just what I wanted and the people were nice, I still wasn’t enjoying the work,” she says. “In fact, I wasn’t enjoying San Francisco anymore. There’s too much focus on ‘hustle culture.’”

Compton worked for such companies as IBM, Pivotal and Atlassian in San Francisco. She was paid well but wasn’t happy. “I worked hard to be a good engineer, but never felt that there was much payoff beyond the money,” she says. “People wanted me to work long hours. There were parts of the work that were interesting, but overall the pressure to complete projects was more than I wanted in my life.”

Like Compton, not everyone who enters the software engineering world, decides to stay. Seventy-three percent of the women who took Capital One’s Women in Technology Survey said they had considered leaving their tech careers at some point due to workplace challenges such as the limited opportunity for advancement or lack of support from their managers. This resonates with Compton. “Working in tech, and especially working in San Francisco, dials up the opportunism in everyone, often to the point where they’ll betray anyone to get what they want,” she says. “I was shocked at just how often I was betrayed by managers, peers, and even friends for the sake of getting ahead. I was never vicious enough to do this to someone else, and that was ultimately part of my decision to quit.”

Compton also found it difficult to change jobs and work for other companies. “The interview process is so ridiculous and difficult, and as I got older, I felt out of place on teams where everyone was twenty-something straight out of college or code school,” she says.

The next generation

It looks like there won’t be a rush of young women eager to take her place. Tracey Welson-Rossman, founder of TechGirlz, a non-profit that encourages middle school girls to explore the possibilities of careers in technology, says, “In the early 2000s ninth grade girls were self-selecting out of tech careers.” There were three reasons for this: girls feeling like they needed to be good at math or science; girls thinking careers in tech were boring or non-creative; and the media portraying people in tech as nerds. “And who wants to be a nerd when they are 14?” says Welson-Rossman.

Welson-Rossman says she wishes more was being done to encourage girls to consider a career in tech. “We need to reevaluate how to increase our efforts,” she says. “The future looks bright for anyone who has tech skills.”

Introducing girls to technology during high school or earlier is important so they can explore a broader range of career options, according to Charles Eaton, the chief of staff at CompTIA, a non-profit that provides education, training, and certification in technology. “Usually there’s a confidence gap girls and women experience when exploring fields dominated by men,” says Eaton. There are ways to reduce this gap, such as starting with a proper introduction to the world of software engineering in school, and providing education and encouragement.

Eaton’s goal is to give girls the knowledge and training they need to succeed in the tech industry. He says, “We need to figure out what they enjoy and what they’re good at, and then hone in on something.” Having role models is a great way to encourage women to become software engineers, according to Eaton. “However,” he says, “a role model has to tell you why they love the job, not just what they do.”

Selina Byeon, a software engineer at Policygenius, didn’t have any such role models to ask. She says, “As an immigrant woman, I did not have software engineer role models growing up.” Byeon, who graduated from high school in New York in 2013, had little experience with computers before college either as there was no computer lab in her school. She discovered the tech professions at college. “I learned what software engineering was and that it could be a career,” Byeon says. “I was a first-generation college student and I felt like I was back in high school having to make important career decisions, but lacking the confidence due to scarcity of information.”

After discovering what a software engineer was, she still didn’t know how to become one. Then a friend joined a coding bootcamp. Byeon’s interest was sparked as she watched her friend become a software engineer. Byeon signed up for the same 17-week bootcamp for women and non-binary students in Manhattan where she learned how to code and build web applications.

Changing direction

Some women “feel pressure to switch career paths so they transition out of software engineering positions and into non-technical roles,” Eaton says. They become managers or project managers, which can take them away from technical roles. Changing careers is not on Byeon’s radar. “I feel like I’m on a great path to reach my goal of becoming a staff engineer,” she says. Becoming a staff engineer would mean taking on a technical lead role.

These days, Compton lives in Vermont, works in marketing at a non-profit, which she loves, and has her own podcast where she talks about her experiences in the tech world. “When I realized I’d worked in tech for 20 years, it was like, ‘Hey, I did it! In fact, I even worked in tech in San Francisco!’ That’s a pretty big achievement and I’m comfortable taking my amazing skills elsewhere,” she says. She advises others to follow their hearts too. “Do it. There is more to life than code. Your work is not your worth,” she says.

At the same time, she encourages women who want to become software engineers to go for it, but to be aware of the downsides. “I found a lot of emphasis in San Francisco on hustling until you make a billion dollars. It seemed to be the sole motivator for everyone around me whether they would admit it or not,” she says. There was also a strong emphasis on what school you had attended. “I got tired of everything being about who you were connected to, where you went to school, how much money you could make and how many hours you could work.”

Being a software engineer can work out well in the right circumstances. “Be careful of where you choose to work,” she says, “and once you get in, help other under-represented, under-estimated people who are trying to break into tech or software engineering.” That’s the kind of advice we can all get behind.

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook on LinkedIn and on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: DEI

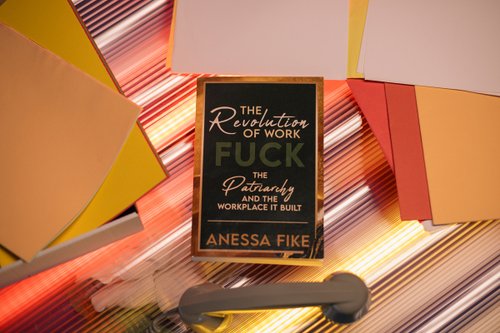

Sh*t’s broken—Here’s how we fix work for good

Built by and for a narrow few, our workplace systems are in need of a revolution.

Dec 23, 2024

What Kamala Harris’s legacy means for the future of female leadership

The US presidential elections may not have yielded triumph, but can we still count a victory for women in leadership?

Nov 06, 2024

Leadership skills: Showing confidence at work without being labeled as arrogant

While confidence is crucial, women are frequently criticized for it, often being labeled as arrogant when they display assertiveness.

Oct 22, 2024

Pathways to success: Career resources for Indigenous job hunters

Your culture is your strength! Learn how to leverage your identity to stand out in the job market, while also building a career

Oct 14, 2024

Age does matter, at work and in the White House

What we've learned from the 2024 presidential elections about aging at work.

Sep 09, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs