Dispelling hourly worker myths with Scott Greenberg

02 jul 2024

5 min

US Senior Editor at Welcome to the Jungle

Barista. Server. Drive-thru cashier. Front desk clerk at the local cinema. Most of us have been hourly workers at some point in our lives, and according to the most recent data, most of us still are. Filling positions not just in retail or hospitality, but in other industries such as manufacturing, health, education, and transportation, hourly workers remain the backbone of the national economy.

They’re notoriously young and often lack the resources that salaried workers are known to be offered. They’re also swarming with stereotypes—unengaged, uneducated, and paycheck-driven. Is what they say true about hourly workers, or is the problem in how we manage them? We sat down with Scott Greenberg, public speaker and author of Stop the Shift Show: Turn Your Struggling Hourly Workers Into a Top-Performing Team to learn more about what makes hourly employees tick.

What makes an hourly worker unique?

Without a fixed salary and often without the same set of benefits as a salaried worker such as paid time off or health insurance, 78.7 million Americans aged 16 and older held hourly wage positions in 2022.

They are also dealing with less job security. From 2017 to 2022, the hourly worker turnover rate rose from 68% to 150%. Their lives are built around precariousness, not just in keeping their jobs, but in keeping set schedules. Their hours and pay are changing regularly since it’s up to their employers to determine their shifts.

“They are constantly juggling from week to week as the schedule changes compared to someone on a salary who has predictable hours and a predictable income,” says Greenberg. “And therefore it’s easier for [salaried workers] to build a lifestyle and access credit.”

So, why would a worker choose an hourly wage over a salary? It’s not just a question of preference. Sometimes, employers choose to hire part-time, hourly workers because it’s cheaper than a team of full-time, salaried employees. Not only can they reduce workers’ hours to make up for lower revenue seasons, but they don’t have to offer benefits to employees working less than 30 hours a week under the Affordable Care Act. The workers who want to work more, who need to work more, often can’t—and on top of that, they’re denied healthcare.

Already, hourly workers are underpaid, with 25.2 million hourly workers under the age of 30 making minimum wage or less. This leaves many hourly workers struggling to get enough work to pay the bills with one job, so they’re turning to poly-employment. Nearly 8.4 million Americans work multiple jobs as of May 2024—more than there has ever been, and the trend is still rising.

Dispelling the myths

Many hourly workers’ experiences fit the stereotype. Greenberg’s daughter, for example, just got her first job at a local burger joint, and he agrees that there is a lot of truth behind our preconceived notions, and much of it comes with age.

It’s easy to imagine the young service worker popping their gum and giving side-eye to anyone who distracts them for their pulp romance novel—but this just isn’t true for everyone, and it’s probably not true for Greenberg’s daughter, either.

“I appreciate using the word stereotype because it’s easy to look at this group and then make these grand statements, that they’re lazy, they’re entitled, or that they’re morons,” says Greenberg. “People are so much more complicated than that.”

Actually, most hourly workers are educated, with 27% holding advanced degrees. His nephew, as a recent UCLA graduate with a molecular biology degree, couldn’t find anything better than an hourly lab tech job.

Many hourly workers have other priorities, too, Greenberg adds, like children, family, or school, which make it difficult to keep a salaried position. An hourly worker can look like Greenberg’s daughter, his nephew, or maybe they’re a 40-year-old single mother just trying to make ends meet.

The role of management

There are a lot of fish in the sea, Greenberg says, but employers need better bait. “If we want to attract and keep people, just offering more money ain’t going to do the trick. And if it does bring you people, it’s not going to make them stay. They need something more.”

The lives of hourly workers are inherently less predictable, with their work schedules changing from week to week—often with fewer hours and less income. And, with so many other priorities, both the workers and their managers tend to treat their jobs as transactional, says Greenberg.

In researching his book, he investigated the issue of accidental management and the lack of formal training in people managers. “They will learn how to run payroll, how to schedule, they will learn those kinds of systemic things, the operational things. But in terms of how to have influence, how to build culture, how to motivate—most people don’t get that training,” he says. “All they know is what they’ve seen from their bosses.”

A recent study found that 66% of managers have no formal training. When employee engagement relies heavily on their managers, what do they need to better support their hourly workers?

To fill this gap, Greenberg is developing HEMS, an hourly employee management system with online courses to guide and certify managers in smart hiring, self-reflection, breaking biases, and employee coaching.

Human, after all

Alongside training, managers need to approach their workers on a human level, Greenberg says, and understand their situation—because, as an hourly worker, everyone’s situation is vastly different. There needs to be a balance between the hard needs—money and benefits, for example—and the soft needs, like belonging and purpose. “I believe that we need to meet employees as individuals, we need to get a sense of their individual circumstances and their individual goals. Are they looking to grow within your company and develop, or are they looking for money for prom?”

If an employee has a very entrepreneurial spirit, hoping to one day own their own business, why not treat their work like an internship, mentoring them alongside their paid job about the broader strokes of management or running a business? Or, if they seem disengaged, try understanding what it is they are looking for from the job. Greenberg believes that having such conversations with employees, even just for a few minutes a week, can help boost loyalty and engagement.

“The problem is that when we neglect their individuality, their unique humanity, then we’re going to have constant problems and constant turnover,” he says. “And still people think, ‘well, the retention problem is because people are lazy or don’t want to work.’”

Indeed, we need to stop treating them all like the stereotypical, blasé burger flippers—because it’s just not everyone’s reality. And even if it was, they’d still deserve a manager that understands their priorities.

“If you’re one of the few people who actually sees them as human beings and can accommodate them, they’re going to work harder, they’re going to be more loyal…and what’s more important as a manager than bringing out the best in your people?”

Company culture shock

Managers aren’t the only ones who can make a difference in an hourly worker’s life. At the company level, a lived-and-breathed culture needs to be implemented—one that makes sense to its workers.

For many companies, culture is just a tagline, a marketing ploy. “These big grand mission statements that no one understands using these big words for values that no one really gets—they don’t really apply,” says Greenberg. “If it doesn’t have meaning for the hourly worker, well, then it’s not going to have any impact, and it serves no purpose.”

But, what is culture, in a broader sense? It refers to a specific set of social norms that exist between two or more people—and everyone has a culture. Everything has a culture, from a country, to a marriage, or even a prison block, he says.

Great organizations, again, take a human approach. “They create a culture that meets the emotional and psychological needs of the people they’re trying to recruit. It means creating a workplace that that gives them a sense of belonging, a sense of purpose.”

Photo by Thomas Decamps for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every week!

Más inspiración: Future of Work

The Bear: When professional passion turns toxic

Carmy's workplace trauma isn't unique...

31 dic 2024

The youth have spoken: South Korea’s push for a four-day workweek

Is this the end of Korean hustle culture?

26 dic 2024

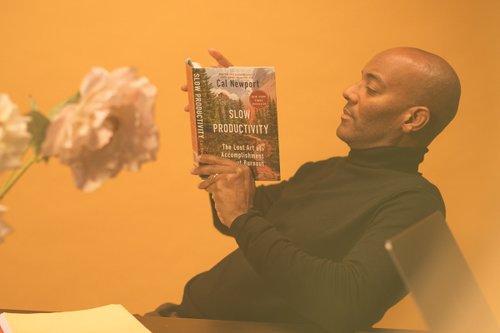

Cal Newport's Slow Productivity: Redefining success in a hustle culture

Is slowing down the key to achieving more?

19 dic 2024

Wellbeing washing: Are workplace mental health apps doing more harm than good?

Workers are struggling with mental health. Are employers approaching it the right way?

19 dic 2024

Dark side of DINKs: Working as a childfree adult

Having children comes with challenges. So does choosing not to.

11 dic 2024

¿Estáis orgullosos de vuestra cultura empresarial?

Dadle la visibilidad que merece.

Más información sobre nuestras soluciones