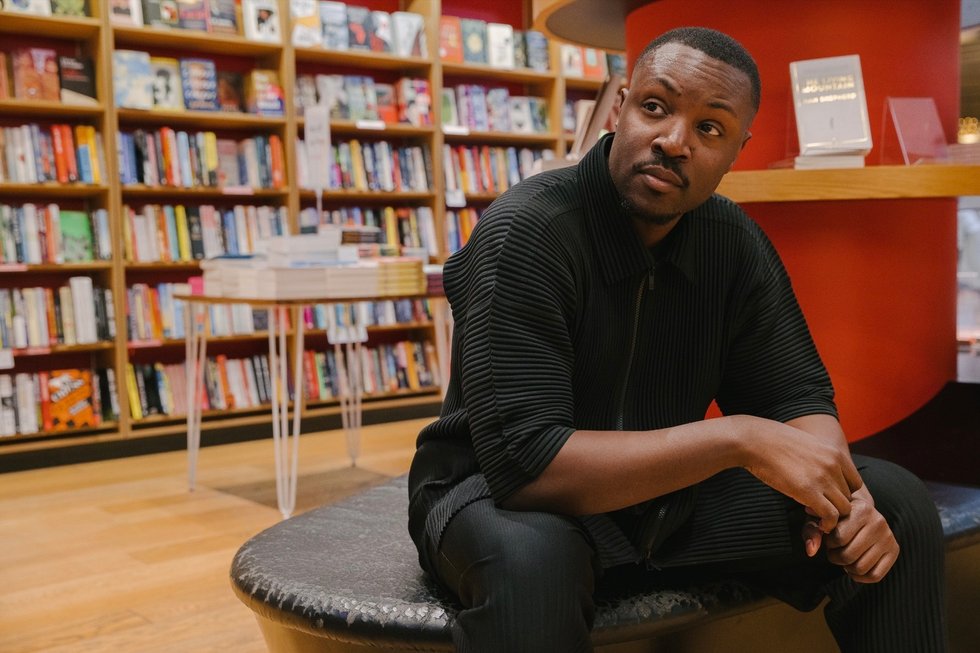

Symeon Brown on ambition and deceit in the new influencer economy

Apr 14, 2022 - updated Jun 07, 2022

7 mins

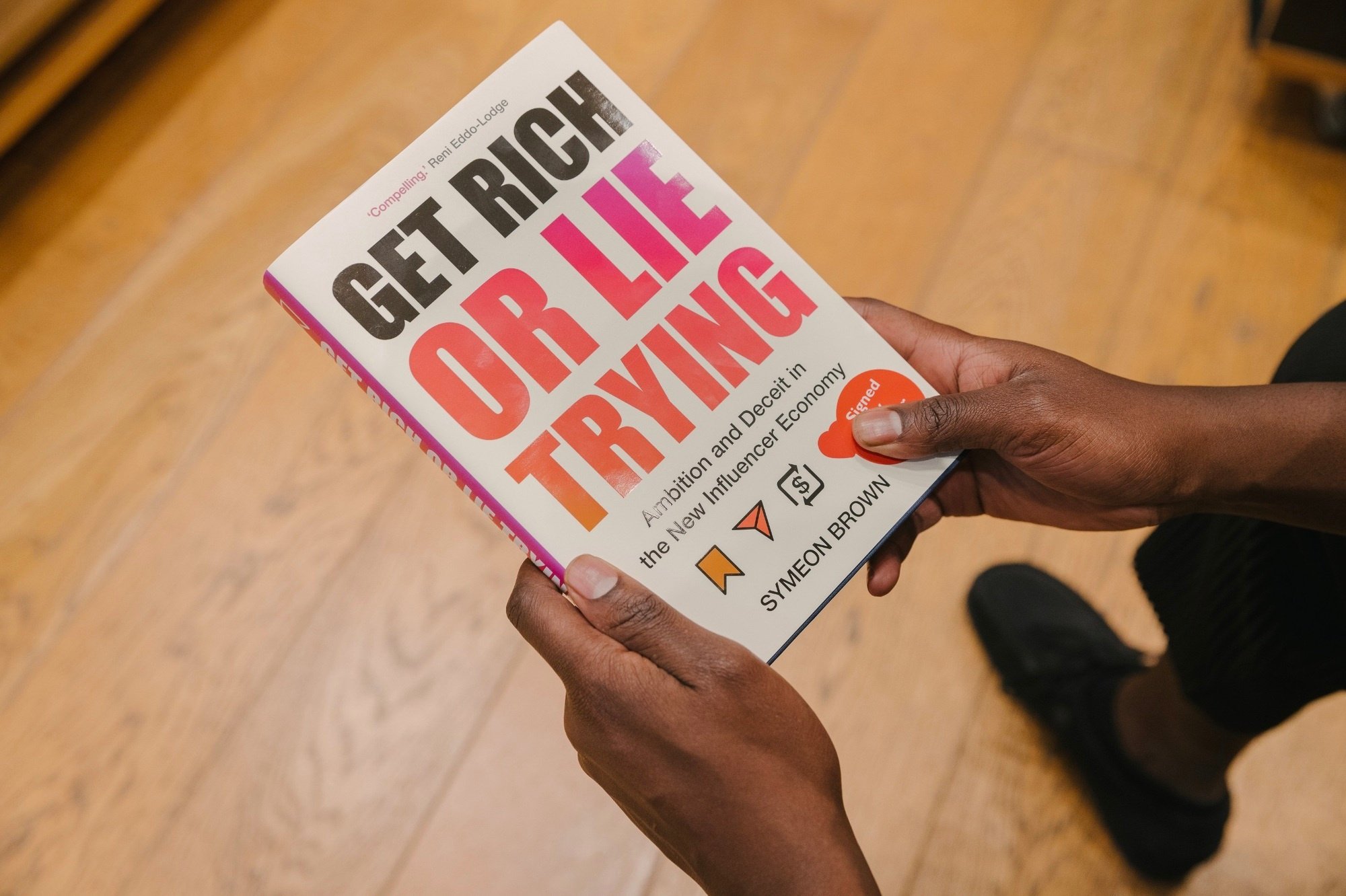

Journalist

The influencer economy hardly existed 10 years ago, in the days before Instagram and before our phones became our 24/7 companions. Now, it’s a $13.8 billion industry. And with brands set to up their influencer budgets and more than one in five children wanting to break into the industry, it’s only going to get bigger. While the influencer industry offers ample opportunities along with the lure of fame, there’s also a dark underbelly—of exploitation and deceit. Symeon Brown, a reporter and journalist with the UK’s Channel 4 News, has dug deep into the stories behind the selfies and follower counts to expose the complex web of the influencer economy. We discussed his findings and his new book, Get Rich or Lie Trying: Ambition and Deceit in the New Influencer Economy.

What inspired you to write this book?

I noticed a lot of young men from non-traditional backgrounds in the city - that is, the working-class inner-city youth - suddenly appeared to be very affluent. They were 21, 22, 23 years old, driving around in very expensive cars, like Rolls Royces and Jaguars. They were presenting themselves online as CEOs and hedge fund bosses based in Canary Wharf (a business hub in London), and they were accruing thousands and thousands of followers, and in some cases, some cases hundreds of thousands.

“Rather than making their money from trading, they were making money by recruiting young people into these devious finance platforms.”

When I started interviewing them, many just said ‘we are influences’. Rather than making their money from trading, they were making money by recruiting young people into these devious finance platforms. Everything from crypto to Forex, and Binary Options (which is now banned). A lot of the products which, according to the FDA rules, were no-win vetting products and they were targeting young people who weren’t aware of what was really taking place, often with the promise of a job. So I began to pull the thread about life online and how working-class young people are turning to the internet to fulfill their ambitions. They’re under huge pressure to achieve when they’re constantly exposed to the trappings of wealth and luxury. I also looked at just how much dishonesty had become a huge currency online, but how it was speaking to a generation’s ambition, and also their sense of distance from the spheres they wanted to be in that have real power and agency - elite capitalism. But of course, they largely have high barriers of entry and have a bias against the people from the kind of backgrounds that I was speaking to for my book. That was what led me into it. From there, what I began to encounter was a story that captured a generation. It captured race, gender, the economy, and technology. It really seemed to speak to everything that was taking place at the time.

“I began to pull the thread about life online and how working-class young people are turning to the internet to fulfill their ambitions.”

What does success look like for influencers?

It depends on the influencer. But in the simplest terms, it’s an income that pays. Often what you see in hustle culture is pressure to be a six-figure earner. Being a six-figure earner is a minimum standard. And I guess that is what a lot of young men are in pursuit of. What I was seeing was a culture that was enthusiastic about needing to be wealthy, and this idea that if a man is not a six-figure earner, he’s not worth it. I guess in the purest sense an income and a livelihood are what determine success in the influencer economy.

“I was seeing a culture that was enthusiastic about needing to be wealthy, and this idea that if a man is not a six-figure earner, he’s not worth it.”

You talk a lot in your book about people from low-income backgrounds turning to careers in influencing. One of your interviewees claimed she was “investing in her future” by getting surgery. In that sense, is influencing a level playing field? The idea that you don’t need a degree or family connections to make money is gone if you have to spend a lot to look a certain way as an influencer.

Yes and no. A lot of young men who get drawn into hustle influencing (crypto schemes or NFT schemes) want to be players in the city, they want to work for Goldman Sachs. They want to work in industries where they pay multiple six-figure incomes and more. But those industries are super-elite and biased, and they recruit in their image. I didn’t see a lot of influencers like that. When I look at influencers I’m looking at people who want to cultivate an advantage. For them, there are ways of creating the illusion of wealth on the internet without having to spend a lot of money. But for the kind of people who are seeking to gain influencer status by being super-attractive or getting a brand sponsorship, yes, there are obviously expenses for all kinds of things—cameras, clothes—and with this comes a lot of debt. For the influencers who end up in pyramid schemes, a lot of them lose huge amounts of money and they obviously find themselves getting scammed.

“[They] want to be players in the city, they want to work for Goldman Sachs (…) but those industries are super-elite and biased, and they recruit in their image.”

Why do you think that influencing is so popular among Gen Z, and to some extent millennials as well? How has the idea of being an influencer changed younger generations’ idea of what their work could be?

The internet is a primary part of the human culture now, especially for people under 40. They meet their partners on apps like Tinder or Hinge. It’s the method of communication and an essential part of our lives. Digital incomes are so present, they seem open and accessible. And as we spend more and more time online, there are constant examples of people saying, how did you make money quickly? The answer is, content. So all these different avenues suddenly open up for people who know that they’re unlikely to get a job at an investment bank without certain qualifications. In terms of venture capital and investment, hardly any women get that money, hardly any minorities get that money. And so the people who are able to really participate in the real Silicon Valley are few and far between. Everybody else turns to alternative hustles online. Covid was a big accelerator for people migrating online and feeling like this was the only game in town.

Influencing certainly looks easier than the traditional career path, but the payoff is that for influencers their identity and their work are deeply intertwined. How does that affect their sense of self?

I think we’ve seen that people have taken their identity from work in the past, so I don’t want to say that these trends are completely new. Everybody increasingly feels like their value is tied up in the work that they do, and society affords you status based on the labor you perform. But with influencing, a person becomes both the product and the salesman. So that becomes an even more personal journey, with the erosion of perimeters around labor. For some people, the way that you look is instrumental to your work, so that’s a further erosion between the public and the private realm, because you lose your anonymity, and your life is opened up as a means of consumption. That creates all kinds of psychological questions.

“Everybody increasingly feels like their value is tied up in the work that they do, and society affords you status based on the labor you perform.”

Do you think there’s any longevity in a career in influencing, even if you are successful?

I don’t think we are anywhere near the peak of influencer culture. Most people still heavily consume the products offline, but we are migrating more online. Even the height of celebrity, bizarrely, is declining. What I mean by that is that we’re in an age where you only need 30,000 followers, according to the ASA, to be a celebrity. So celebrity is far more accessible, and a lot of people are generating a livelihood by cultivating followers, effectively becoming micro-celebrities. But in terms of what it takes to be a household name now, that is far harder. You could be in a room with somebody with 100 million followers, and nobody has any idea who they are, because there are just so many ecosystems within influencing. Celebrity as this all-encompassing thing that everybody can point to as a kind of marker is declining. And this is only the beginning.

At the height of the pandemic, a lot of people went online to make a living. Did that give the influencer economy a big boost?

Everybody was looking for content. We saw increases in people’s time spent online on Instagram. There was a rise in people searching “How to be a YouTuber.” In many cases, the ones who got rich were obviously the platforms (YouTube, Instagram), so there’s a huge inequality between the users and the platform itself. The people really getting rich are the shareholders—and that’s a narrow elite.

“The people really getting rich are the shareholders—and that’s a narrow elite.”

What are the mental-health impacts of influencing that you observed?

That wasn’t something I looked at in detail. But a lot of the people I spoke to were developing anxiety and an unhealthy relationship with their phones. They had a sense that the world was constantly watching them. These are areas of concern.

The influencer economy is like a Wild West. There are no checks or balances that can be used to curb exploitation in the industry or hold influencers to account over what they are trying to sell.

At present regulators don’t know what to do. There are channels with millions of users, so the regulators are completely out of their depth in terms of being able to monitor it. But software is super-powerful, and I don’t really think we’ve scratched the surface of what is possible. But that obviously requires a sense of urgency.

Many entrepreneurs are young, and they’re struggling to navigate the ethics of their business choices. But is there a way to influence with integrity?

For me, it’s more about what the platforms incentivize. We’re all on platforms in which they’ve built in rewards for us to act in a certain way. If our material needs are not being met, if you are under pressure to be successful and be wealthy and their energy bills are going through the roof - you are more likely to be drawn to these kinds of money-making schemes. You just have to look at the circumstances that make people behave in a certain way. It’s not about individuals doing X, Y, and Z. The question is, what are the structures that lead them to behave that way? That, for me, is really the story.

Photos: Betty Zapata for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook on LinkedIn and on Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: Inspiring profiles

Be real, get ahead: The power of authenticity in your career

Pabel Martinez shares insights on how to allow yourself to be yourself, find your voice, and deconstruct stereotypes at work.

Apr 25, 2024

The professionalism paradox: Navigating bias and authenticity with Pabel Martinez

Pabel Martinez challenges the conventional norms of professionalism by unraveling the complexities of workplace discrimination.

Mar 11, 2024

How play can make you happy, creative and productive at work

Work-life balance usually means separating work and play, but it might be a better marriage than you think...

Nov 07, 2023

Project Street Vet: Caring for the unseen paws of Skid Row

Providing vet-to-pet care in some of California's largest homeless communities, Dr. Kwane Stewart shares the ups and downs of his remarkable work.

Aug 29, 2023

Girls learn how to have fun – and funds – by investing

A Danish trio is fighting gender inequality... on the stock market. We had a chat with one of the co-authors of the book Girls Just wanna Have Funds

Jan 30, 2023

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs