CEO seeks organized Taurus: China’s crazy recruitment criteria

Dec 14, 2023

5 mins

YL

Journaliste internationale

CH

Journaliste internationale

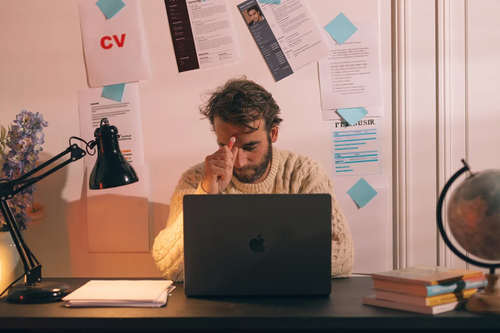

Have you ever had your job application rejected because your star sign was incompatible with the CEO? Or because the recruiter thought your birthplace would bring the company bad luck? In China, where unemployment among young people is rising fast and competition for jobs is extra fierce, this kind of criteria can make or break your job application.

Buxian’s story

Buxian Tutou is still reeling from experiencing it first-hand. The 22-year-old graduate recently went through two shockingly discriminatory recruitment encounters. “The first one happened last March, during a job interview for a video games company,” she says, using a fake name for fear of not being able to find a job. “After the standard personal questions, like whether I had a partner or not, the recruiter asked me for both my Western and Chinese star signs. The look on his face when I gave my answer said it all.”

That was the end of the recruitment process for her. Without being able to get feedback from the company, it’s hard to be sure of exactly why she was passed over, but Buxiang found out later that some bosses preferred a Taurus or Virgo because apparently, they’re more ‘trustworthy’.

The second incident was with a headhunter who wanted to know when and where she was born. “It just felt a bit off,” she recalls. The hidden agenda? To test for star sign compatibility. Only people whose star sign was said to complement the boss advanced to the next stage.

An unknown unemployment rate

Star signs, birthplaces, and even blood types have long been used by matchmakers seeking to make the perfect love match. However, some Chinese recruiters use this selection criteria to find the perfect match for a company.

A dramatically rising unemployment rate plays a supporting role in these less-than-scientific methods. Last June, China posted record unemployment for the 7th consecutive month: 21.3% of 16–24-year-olds in urban areas were looking for work. Two months later the Chinese national statistics office announced that they were simply going to stop publishing the data. According to spokesperson Fu Lingui, the questionnaires used to collect the data needed to be, “improved and optimized.”

In all likelihood, the figures themselves were the issue. “It’s feasible that, to avoid any kind of social issue or difficulty, the Chinese government decided to stop publishing certain data,” explains Peter Ho, Chinese economy researcher at the London School of Economics (LSE).

Despite the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions, the country is facing various economic challenges. “Employment opportunities in sectors which have represented more than four-fifths of total employment—technology, property, and private education—were harshly affected by lockdowns during the zero-Covid period and the government’s strict control measures,” says Ho.

Another exacerbating factor: a record number of graduates recently entered the Chinese labor market. Around 11.6 million people finished university this summer, widening the potential candidate pool.

Across the country, headhunters confirm that job vacancies have dropped. “Finding jobs for our clients was easier before the pandemic than it is today,” explains Mavis Mau. He lives in the huge city of Guangzhou and works as a headhunter for IT companies. “Many companies are more careful when it comes to employing a new person because of the costs. Some are even reducing their workforce.”

With a bleak labor market, competition becomes fierce. “The total number of resumes we’re receiving has increased. Employers have so much choice they can be more demanding during the recruitment process,” explains Mau

Women have it even harder

Some employers might be looking for a certain blood group, but luckily others prefer experience or a prestigious degree. But for women who are no longer considered young, there are even more obstacles. “I started to find it much harder after I turned 28,” recalls Veronica Yu, 31 from Beijing. “I was eliminated at the first stage of recruitment because my age or gender didn’t fit what they were looking for,” she shares. An acquaintance told her that she hadn’t been invited to interview because only candidates under 27 were eligible.

As a single woman, finding a new job is becoming increasingly difficult for Yu. “Some headhunters are so brazen they even write ‘man’ in brackets next to the job title. It’s nuts!” And if she finally gets an interview, they ask her never-ending questions about her marital status and whether she wants children. “Why should I have to tell a company whether I’m married or want to have children? I just don’t get it.”

As if finding a job isn’t hard enough, Yu, who works in marketing has had to change jobs several times over the last few years—the reasons: bankruptcies and in one case, serious harassment. Ever since, recruiters constantly criticize her resume for being full of gaps. “Just because I only worked for an employer for a short time, doesn’t automatically mean there’s something wrong with me. You can’t just treat me like a defective product,” she says, angrily.

It may seem at odds with the precarious market, but more and more young people in China are quitting their jobs, sometimes after just a few days. Just like everywhere else in the world, younger generations expect more from their job.

Superstition is old fashioned

Li Luojie heads up recruitment for a Chinese IT company. He admits he’s heard tell of candidates who felt discriminated against because of their age or gender. “It depends on the industry. The tech industry continues to innovate, especially with artificial intelligence. People need to be able to handle this constantly evolving industry, so older candidates are often excluded.” Explains Li, who works in Shenzhen in the south of China.

“There’s also a preference for men,” he admits. “In China, we tend to feel that long working hours are less suited to women as they aren’t conducive to family life.” Chinese people work on average 48.7 hours a week. However, the tech industry has what they call a ‘996 working culture’, working from 9 am to 9 pm six days a week. Young people even joke about a ‘007 schedule’: working seven days a week, 24 hours a day.

Li is quick to add that he applies strict, standard criteria, during his recruitment process. “Only candidates with degrees from the best universities will be invited to interview.” For him, using superstition is out of touch. “There are more and more millennials and Gen Z’ers in management positions. When they hire, they value professional experience and education over personal relationships or traditional horoscopes.”

Stepping back into childhood

With or without horoscope readings, the unemployment problem for young people isn’t going anywhere. The Chinese magazine Caixin estimates that the unemployment rate for under 25s will increase by 1 to 3% every month over the next four months. For Professor Ho at LSE, the situation is pressing, but it’s not yet disastrous. “Although there are serious concerns about the Chinese economy and unemployment among young people, I still think it’s early days to be sounding the alarm on imminent economic collapse.”

For its part, the government is aiming to create 12 million jobs this year. The local municipalities will need to roll up their sleeves and recruit 16% more civil servants than in 2022.

However, the boost won’t be enough to eradicate unemployment in a country where more than 80% of urban jobs are in the private sector.

In this economic landscape, some young people are even giving up the idea of getting a traditional job in a company to return to childhood. They’re leaving the big cities to return to their parent’s homes and help them shop, cook, or clean for a little pocket money. It’s certainly a much slower, calmer pace of life.

Translated by Debbie Garrick

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every week!

More inspiration: Follow hiring trends

Hilke Schellmann exposes the flaws in AI that control your next job offer

AI tools promise fairness in hiring but often fail. Hilke Schellmann reveals how these flawed systems shape careers and why transparency is crucial.

Dec 23, 2024

How AI coaching can give young job hunters an edge

Considering a career coach but don't have the resources to pay for one? AI might be able to help.

Dec 12, 2024

Are internships replacing entry-level jobs?

If an entry-level role requires years of experience, young job hunters are already at a disadvantage …

Mar 06, 2024

Swipe right for success: Using dating apps to job hunt and network

Genius networking move or master manipulation?

Jan 30, 2024

Job search in 2024: A candid look at the US job market

Are layoffs coming to an end? Will you finally land a job in your dream industry? Let’s see what the market has in store …

Jan 22, 2024

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs