Learned helplessness: When a will doesn't provide a way

Oct 20, 2022

3 mins

That’s it, you’ve made the decision. You’re going to change your life, switch jobs, take up meditation and start exercising. It’s time for a reset, and you’re determined! Then a few months go by—and not only haven’t you made any progress, you haven’t even taken the first steps. “Tomorrow,” you tell yourself. “Or Monday.” After a while longer, as the daily grind continues and you find it harder and harder to take initiative, you finally just give up on the idea entirely. It wasn’t a question of willpower because that’s there. So why quit before having tried?

Learned helplessness: A false belief that freezes us in our tracks

The motto “Who wants to, can” is not entirely true and does not take into account the myriad psychological blocks with which a person may be coming to the table. In the 1960s, a psychological experiment by American psychologists Steven F. Maier and Martin E. P. Seligman was able to prove a phenomenon called learned helplessness. Learned helplessness is when a series of negative outcomes or stressors causes someone to believe that the outcomes of his or her life are out of his or her control. The result is a person who, upon realizing they cannot avoid bad things that may happen in the future, decides those things are inevitable.

Before proving learned helplessness in human beings, the experiment proved the phenomenon existed in dogs. In the initial experiment, two dogs were placed in similar but separate cages. In each cage, there was a lightbulb, a lever and an electric floor that emitted mild electric shocks. The dogs experienced different situations though:

- Dog A: Just after the light dimmed, an electric shock was sent through the floor. When Dog A pressed the lever, the shock stopped immediately. Dog A was taught that he could act to stop the shock.

- Dog B: Just after the light dimmed, an electric shock was sent through the floor (same as Dog A). However, when Dog B pressed the lever, nothing happened. Dog B was taught that his actions could not stop the shock.

After this process was repeated several times, Dog A knew that an electric shock would occur as soon as the light dimmed. Through conditioning, he learned to press the lever to avoid it. By contrast, Dog B resigned himself. He lied down, whined and received the shock.

When they placed the two dogs together in a new cage and performed another test, their behaviors differed again. This time the lever was removed and the cage was divided into two parts: one side had an electric floor and the other did not.

- Dog A: As the light dimmed, Dog A who believed he could act to avoid the shock explored the cage. He walked to the other side of it and found safety. Every time the light dimmed after that, he knew to cross to the other side of the cage.

- Dog B: When placed in the second cage, he behaved normally. He didn’t have physiological issues from the previous experiment. However, as the light dimmed, Dog B remembered he couldn’t do anything to stop the shock in the previous cage, so he didn’t even attempt to avoid it in this one. He didn’t cross the cage to safety. He gave in to the belief that he’d get shocked, thus developing learned helplessness.

Good and bad surrender

Learned helplessness is a set of beliefs that makes us think we can’t do anything in certain situations, so we stop trying altogether. Essentially we quit before we start. The human race is particularly sensitive to learned helplessness: Many people don’t take an initiative for change when they believe certain outcomes are inevitable. Though this conclusion can be logical, it becomes less rational when we don’t even pause to question our beliefs.

Should I give in to the notion that I can’t go back to school because I might be too old and my days to start a career are over? Is this belief true? With the changing work environment, shouldn’t we challenge the mindset that pushes us to surrender to hypothetical situations too quickly?

Though sometimes it’s good to know when to resign the time or effort you’ve been putting into something—for example, if you started a company or professional endeavor that doesn’t generate any profit after an extended period of time, maybe it’s a sign to take a step back and regroup—more often than not, we are more than capable of shaping our professional lives (and personal, for that matter) through action and self-empowerment.

Translated by Lorraine Posthuma

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

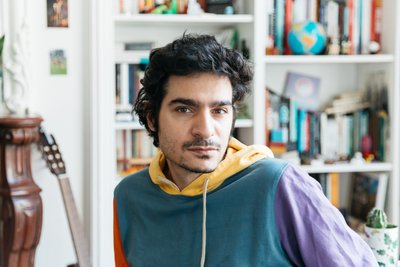

More inspiration: Albert Moukheiber

Doctor in neuroscience, clinical psychologist and author

Work Psychology : The fallacies of binary thinking

Can humans be creative and analytical at the same time?

Dec 19, 2022

What if our search for meaning at work is meaningless?

Welcome to the Jungle's psychology of work expert asks if corporate promises of meaning are merely pseudo-deep bullshit...

Oct 24, 2022

Work psychology: Don’t be afraid to voice your doubts at work

Often feeling unsure about your decisions, and yourself? Well, that might be your greatest professional asset...

Jun 29, 2022

‘Six months of working followed by two weeks’ holidays! That’s ridiculous.’

What if our balance has been wrong from the start? We spoke to Albert Moukheiber — doctor in neuroscience and clinical psychologist.

Oct 14, 2021

Psyched: is the quest for success making you unhappy?

Is professional success the sole reason for your life's satisfaction? Dr Albert Moukeiber explains why this could be harmful to your mental health.

Jul 22, 2021

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs