Navigating your career while managing chronic illness

Dec 24, 2024

6 mins

JB

Writer, translator and journalist

The early years of Sarah Berthon’s career were beset by chronic fatigue, constant migraines, and joint pain. All of which had a profound impact on how she could perform at work. But by the time she hit her 30s, these symptoms had become a major barrier to continuing in employment. She was struggling. And, she ultimately lost her job and her career.

Berthon was eventually diagnosed with Ehlers-Danos syndrome (EDS), a genetic condition that affects the connective tissues of the bones, skin, and organs. She was also diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), which often coexists with EDS, and which causes a person to feel dizzy or even faint when standing up after a period of sitting or lying down. As with nearly all chronic conditions, there is no cure, only ways to manage the symptoms.

Living with chronic illness is challenging. It’s a reality faced by nearly 129 million people in the US alone. From the onset of symptoms to diagnosis and ultimately finding effective treatment (which there may not even be) can be a long and stressful process. However, in the meantime, a person can be expected to carry on living and working as usual.

The reality of working

“Medical appointments can be all-consuming,” says Berthon. An appointment on paper may only be an hour with a specialist. But the reality is far from that. For example, that hour doesn’t account for the travel to and from the appointment or even the time spent in the waiting room. It also ignores the fact that a person may need to prepare by going on a special diet or fasting. Then, after the appointment, they may be experiencing pain due to an invasive procedure, and/or anxiety and stress due to difficult conversations with consultants. “It’s not just a case of taking an hour off work. These appointments can affect you for two or three days,” Berthon shares.

A person who knows all too well about the challenges faced by appointments is Jacob Kendall, who provides support and guidance to patients and health professionals. “I have to attend probably 10-20 medical appointments a month—and they’re all during working hours,” he says. Kendall lives with congenital aortic valve disease (a heart condition) and chronic back pain.

There’s also the issue of the medical procedures themselves, and the recovery—both physical and mental. Kendall has had two open-heart surgeries. He explains that after these operations, he experienced heart palpitations and a tight chest. “It’s anxiety. It can convince you that you have other things wrong with you too.”

As with so many physical conditions, the mental component can often be overlooked. However, around 30% of people with long-term health conditions also have mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. “My back pain is rarely ever severe. But it’s so constant that it just nags away at me like a thorn in my side. This affects my ability to concentrate,” Kendall explains.

“Pain is very distracting,” Berthon agrees. “Likewise, chronic fatigue can be exhausting, and brain fog can make concentrating difficult.” However, she stresses that all chronic illnesses are different and each person’s experience of illness is unique. The latter can often be disregarded by colleagues, who can underplay conditions and dish up advice based on what they’ve read in the media or the people they know around them. Kendall confers that people around you tend to show “sympathy but not empathy: they care but they don’t understand.”

It can also be difficult for managers and colleagues to understand the nature of living with an illness as many conditions fluctuate. “One day you might have a good day. Then the next, you’re struggling to get out of bed. That’s why it’s important to be able to work on the right tasks at the right time,” explains Berthon.

To disclose or not to disclose

Knowing whether to disclose a medical condition to your employer or not can be tough. However, as Berthon says, this is always a personal decision and one that should be taken with no pressure. She explains that she chose to disclose her medical condition after feeling she was having to ask to work from home “too frequently for her liking.” She says, “I just needed to talk to someone and explain what was going on.”

As for Kendall, he always tries to be as open as possible about his health in order to normalize chronic illness and pain. In fact, he states that many colleagues have thanked him privately for being so open as they haven’t felt comfortable talking about their own conditions.

Indeed, there are benefits to disclosing your medical status. “If you think there’s something that your organization could do to support you better, then that can be a good time to disclose your medical condition,” Berthon explains. However, she stresses that it’s important for a person to know in advance how they feel they could be supported. “Without knowing what support you need, it’s very difficult for the organization to give you that support,” she adds.

Berthon also points out that many chronic illnesses fall under the classification of a disability and by disclosing this early on, you can get the support in place for the interview process when applying for a job.

Finding support and making changes

Ultimately, support can vary depending on an illness. For example, Berthon recalls that while working at a previous job, she managed to identify that the overhead lights were acting as a trigger for migraines. Therefore, her company gave everybody desk lamps and colleagues would turn off the main light when she was in the office. “The organization was really good. No one made a big deal. It was all done without me even asking,” she says.

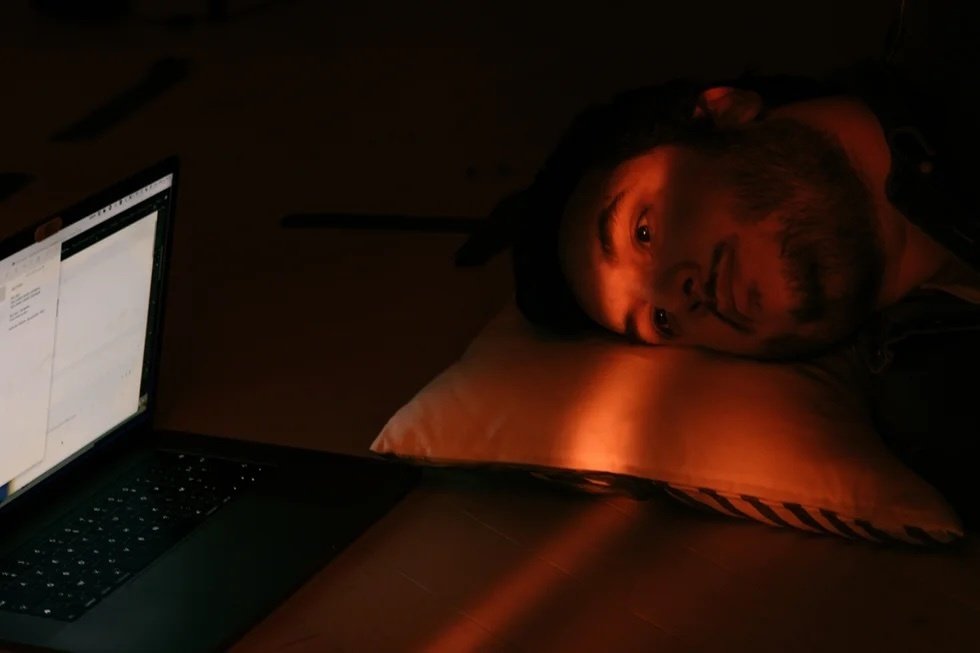

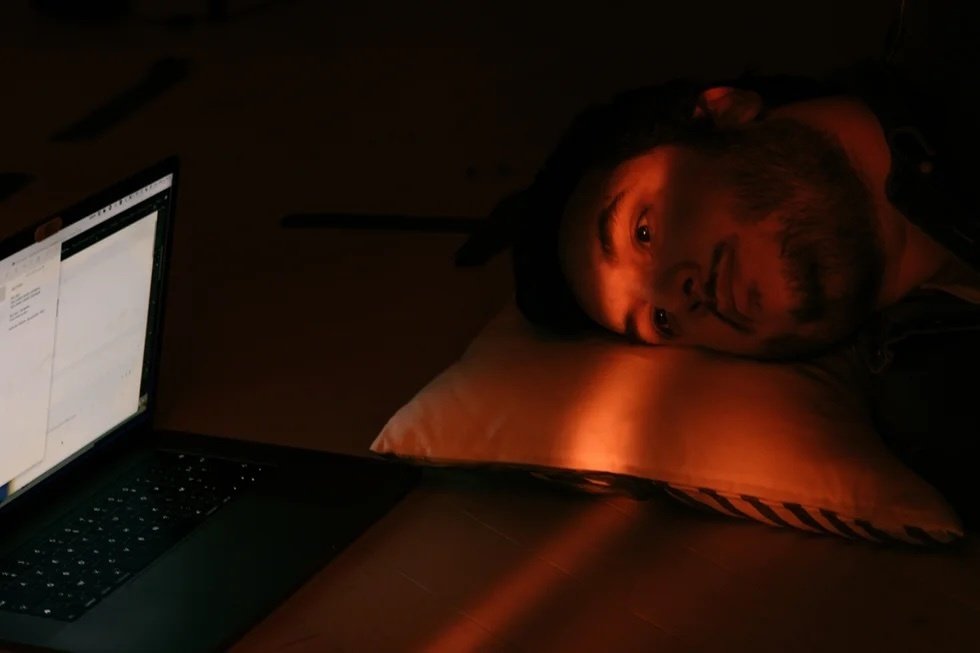

Flexible and remote working can also be a godsend for people with chronic illnesses. “When I’m working from home, I can switch from sitting to standing to even lying down while getting work done. If I have to go into an office that becomes a lot more difficult,” says Kendall.

Berthon empathizes with this. Due to joint pain from her EDS, if she stays in one position for too long, there can be complications. Similarly, due to issues with her blood circulation, she sometimes needs to walk around to get her blood moving or even lie down for a bit, which can help the blood reach her brain. This isn’t practical when working from an office.

Likewise, Kendall highlights companies recently implementing camera-on policies during video calls as being another potential reason for needing accommodations. “If I’m lying down to alleviate back pain, it doesn’t make sense for me to be on camera because it’s just awkward,” he says.

Kendall explains that people can receive such accommodations after requesting them from the right departments. However, he argues that in an ideal world, workers wouldn’t have to go through these long official processes. “There’s an emotional and mental burden to seeking accommodations,” he concedes.

It is for reasons like these that Berthon believes that there can be great benefits for companies to receive training around disabilities and chronic illnesses. “This is something that affects so many people. Anybody can develop a chronic illness. It’s about enabling everybody to have the same access to work as everybody else.”

Changing the system

Berthon, through her initiative Excel Against All Odds, now provides this training to both companies and employees in the UK. She believes that there needs to be a change in corporate culture from the top down. It’s also important for people with chronic illnesses to know there is support out there. For example, in the UK, there is the Access To Work government scheme which provides grants to help people find or stay in employment. “It’s a brilliant scheme but nobody knows about it. It can also take a long time to go through the whole process. But it can be a big help,” says Berthon.

On the other side of the Atlantic, where Kendall provides support for both patients and health professionals, he concedes that it’s absurd that the US is so “dependent on for-profit healthcare compared to other industrialized countries.” He feels that the system in the US is not designed for people with chronic illnesses. “But, I totally believe that the system can be designed such that organizations don’t lose profit, while providing adequate resources for their employees.” Ultimately, money is the bottom line.

However, as Berthon points out. There is indeed a strong business case for employing and supporting people with chronic illnesses: companies end up building better products and services for their customers.

“If you’re designing a banking service, you want a team that understands what it’s like to do banking with a chronic illness. Because many of your customers will have one.” Likewise, Berthon states that people with chronic illnesses often develop amazing strengths, adaptability, and determination, which become an asset for teams. “For example, I now have a superpower for getting a lot down in a very short amount of time because I know I have a limited time frame.”

As Kendall says, “There’s certainly a wisdom that comes from having these illnesses, but damn does that wisdom come at a high cost.”

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every week!

More inspiration: Physical health

The best equipment to help you get exercise without leaving your desk

A sedentary lifestyle can lead to serious health problems. So, how can you stay fit while still at your desk?

Nov 09, 2023

Glued to your desk all day? Try these discreet exercises

Laptop-based work can mean freedom and comfort, but a sedentary lifestyle also brings a host of health risks...

Oct 18, 2023

How the world of work is getting better for veterinarians

Though typically not considered a dangerous profession, veterinary services rank among the highest industries for non-fatal injuries

Oct 04, 2023

The dynamic benefits of walking meetings

As our jobs become more flexible, workers are finding new ways to improve their mental and physical health

Oct 03, 2023

Digital eye strain: You are not alone

With the average American spending more hours in front of the screen than sleeping, computer vision syndrome has become a folk illness.

Oct 04, 2022

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs