Psyched: why we always imagine the worst

Jul 19, 2021

4 mins

In two weeks, you’ll be giving the biggest presentation of your life. You’ve spent months working on it and the whole office will be there. You’re ready: the slides are all set. But at home, as you settle down for the night, your mind goes into overdrive. You start imagining every worst-case scenario possible: your computer will crash, the projector will explode, and everyone will laugh at you. In other words, it’s going to be a major failure. Although you’re ready—and you know you are—you still imagine the worst. How is that even possible?

Stress is a very peculiar thing. It’s as though your brain were working against you. But if you look into the distant past, you might see how thinking the worst could well be a useful psychological asset. Let’s try a kind of experiment. Imagine you’re living a few hundred thousand years after the evolution of our species, Homo sapiens sapiens. You’re foraging for food in the forest. Suddenly, you hear a noise between the trees. You don’t know what’s making that noise—so you have to imagine it.

You can imagine it’s something good—like the wind—or you can imagine the worst: it’s a predator. If you imagine it’s the wind and get it wrong, it could cost you your life. Imagining a predator and running off, on the other hand, won’t cost you that much.

Stomach ulcers and zebras

From an evolutionary perspective, imagining the worst has an adaptive advantage. Some psychologists consider that this evolutionary explanation is the reason why we imagine worst-case scenarios whenever we’re anxious. It’s a type of self-defense in the brain called the precautionary principle. It was well suited to hunter-gatherer societies—when dangers had deadly consequences.

In today’s world, most adults can go their whole lives without ever crossing paths with a predator. My PowerPoint presentation won’t pounce on me as I sleep. What we’re dealing with here is known as “adaptive mismatch”. It’s an adaptive lag between a reflex that made a lot of sense in one context that has now become detrimental in another.

If you start stressing out weeks before an event, your mind will have thought ahead so much, it will go blank or be paralyzed with fear.

At the same time, stress isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In some situations, it can be a lifesaver. That’s when we call it “eustress”. What’s the difference between bad and good stress? Temporality. As the American neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky explains in his book Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers (1994), stress in the animal kingdom tends to be short-lived. Take a lioness hunting a gazelle, for example – it takes 10-15 minutes, tops. If the gazelle isn’t stressed out, it will be killed. Stress in that context is good because it’s akin to preparing actions for survival.

In humans, stress takes a lot longer and, according to Sapolsky, this temporality is what makes it problematic. If your insane presentation is tomorrow and you stress out the day before, it’s no big deal. But if you start stressing out weeks before an event, your mind will have thought ahead so much, it will go blank or be paralyzed with fear. In other words, you’re unlikely to succeed.

So, what’s the best way to stop imagining the worst?

1. Embrace uncertainty

If you’ve ever tried to tell someone who’s stressed out that everything will be fine, you’ll have noticed that it doesn’t work. In fact, this approach never works: they’ll probably freak out even more. If I imagine a lion is coming to attack me and you say, “No, Albert, don’t worry, it’ll be fine,” I’ll just conclude that you don’t know the first thing about my situation.

If we bring our example into the present, the same thing happens. Your friend can reassure you and tell you this will be your best presentation yet – but you’ll just conclude that they know nothing. And the worst thing is, you’re right! Nobody can know how an action will unfold and, this time, no self-defense mechanism in your brain will be able to stop it. You just have to embrace the uncertainty by postponing your stress.

2. Adopt a self-distancing attitude

Solomon was a biblical figure renowned for his wisdom. In the Old Testament, he is characterized as a prophet and king of Israel whose judgment helps his kingdom to prosper. But in his private life, Solomon struggled to make the right decisions – so much so that his life became a living hell – which eventually led to the collapse of his empire. In the 21st century, psychological researchers wanted to know whether this passage from the Bible had any scientific value. After some empirical experiments, they managed to prove that we are indeed much better at giving advice to others than to ourselves. They called this phenomenon “Solomon’s paradox”.

The most recent study on Solomon’s paradox was carried out by Igor Grossmann and Ethan Kross in 2014. In a series of experiments, psychologists asked students to imagine a scenario in which a person learns that their partner is cheating on them. When students put themselves in the shoes of the person being cheated on, they reacted as they probably would in real life – instinctively, with anger. By contrast, if they imagined it happening to one of their friends, the subjects had a more reflective attitude. This is called psychological self-distancing. It’s about imagining that your problem is someone else’s rather than your own. In King Solomon’s case, he might well have saved his throne if he’d imagined himself going to seek advice from another king.

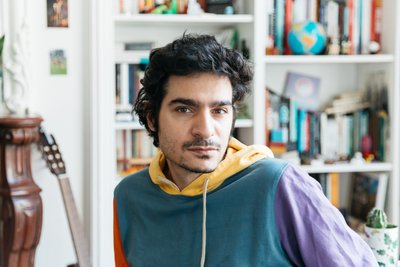

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: Albert Moukheiber

Doctor in neuroscience, clinical psychologist and author

Work Psychology : The fallacies of binary thinking

Can humans be creative and analytical at the same time?

Dec 19, 2022

What if our search for meaning at work is meaningless?

Welcome to the Jungle's psychology of work expert asks if corporate promises of meaning are merely pseudo-deep bullshit...

Oct 24, 2022

Learned helplessness: When a will doesn't provide a way

In the 1960s, two American psychologists figured out why willpower isn't always enough to turn our lives around

Oct 20, 2022

Work psychology: Don’t be afraid to voice your doubts at work

Often feeling unsure about your decisions, and yourself? Well, that might be your greatest professional asset...

Jun 29, 2022

‘Six months of working followed by two weeks’ holidays! That’s ridiculous.’

What if our balance has been wrong from the start? We spoke to Albert Moukheiber — doctor in neuroscience and clinical psychologist.

Oct 14, 2021

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Explore jobs