How our burnt-out society can finally get some rest

19 mars 2024

16min

Journalist and translator based in Paris, France.

The world is spinning faster. Not literally—that theory’s been debunked—but there’s a widespread feeling that there’s more stuff to do and far less time to get it done. This isn’t some collective hallucination: a Microsoft survey of 31,000 workers found they participated in three times as many meetings and calls once Covid hit. In October 2023, Slack reported that employees spend over a day per week on average just drafting emails. And, of course, everyone is side-hustling like crazy to make up for inflation and money lost during lockdowns. We’ve boosted our number of daily tasks, but not our bandwidth.

So now we’ve got mass burnout on our hands, and the purported cure is: rest. Suggestions for capitalizing on downtime range from micro-breaks to week-long vacations. But the machine that created this rampant, lingering fatigue keeps going. What’s the point of recovering from recurring exhaustion only to jump back into the source of our stress?

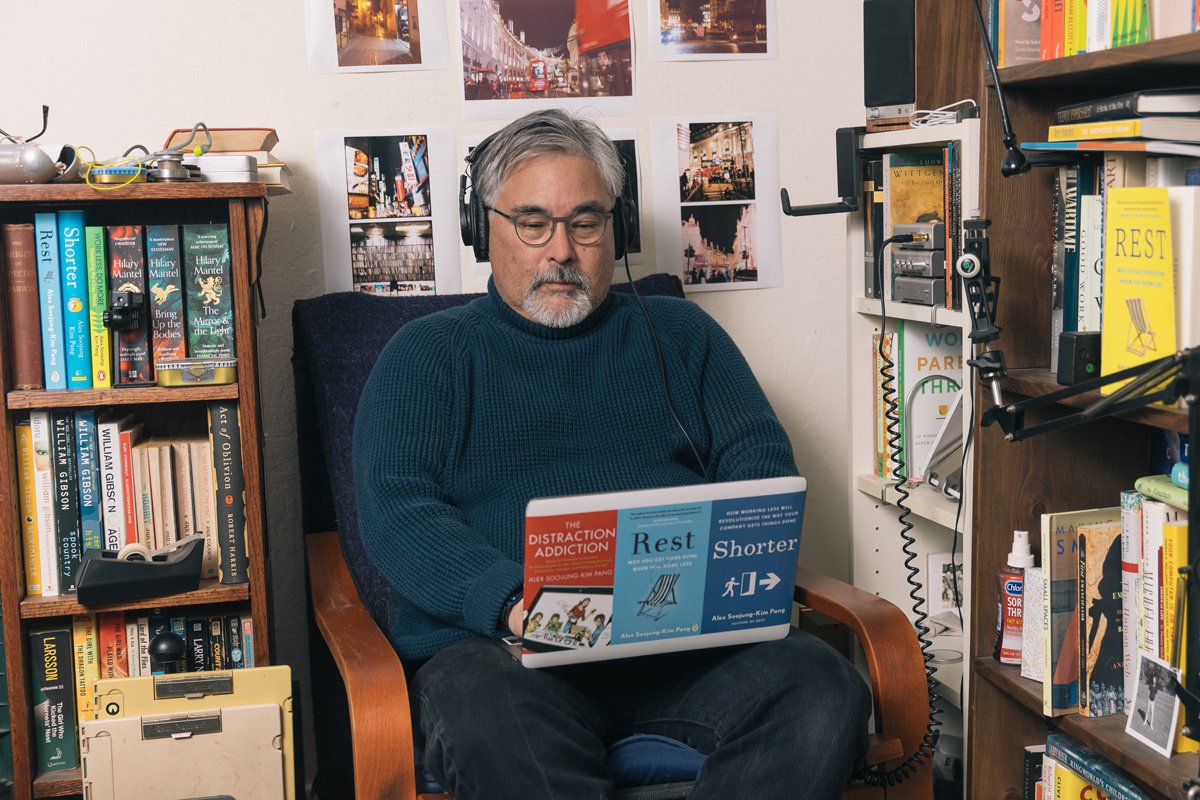

At some point, solutions for rest need to be durable. To understand our options for chilling out long-term, Welcome To The Jungle spoke with Dr. Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, a technology forecaster, corporate planner, and program director at 4 Day Week Global, where he designs some of the big four-day workweek pilot programs you’ve heard about in the news. Author of the books Rest and Shorter: Work Better, Smarter, and Less— Here’s How, he talks about how we can sustainably unwind as individuals, what we can change together, and a little-known practice called “contemplative computing.”

“Work has gone from something that happened in discrete periods to a fine powder that’s now blown across all of our days.”

In your opinion, what are the culprits of overwork?

The challenge with overwork is imagining a future of work that’s different. There are a whole bunch of different interlocking pieces that make overwork and long hours seem inevitable and inescapable.

First of all, you have a long-standing thread in American culture, building on the Protestant work ethic that has seen long hours as a source of economic good. If you read William James’ essay “Gospel of Relaxation,” where he compares American and European work culture in the 1890s, he talks about Americans’ obsession with work in a way that sounds very 21st century. So it’s partly this long history that underpins our modern situation.

Overwork was once a problem for particular professions, like medicine or law; now it’s a public health issue. Particularly since the 1970s, with the decline of the labor movement and labor representation, and the rise of the gig economy and its predecessors, work has become increasingly unstable and subject to ever-greater highs and lows in the markets and in people’s lives.

In the 1950s, the two biggest companies in America, General Motors and General Electric, were both run by guys named Charlie Wilson, both of whom had started in the proverbial mailrooms of their respective companies and worked their way up. And that’s what success looked like a couple [of] generations ago, right? You start at the bottom, you pay your dues, you work your way up, and then you make it to the corner office or wherever.

With the explosion of the tech and finance industries, particularly in the 1980s, you see that replaced with a different career model, one in which success is not something that happens over the course of your entire life. It happens very quickly. You’ve got business memes like the Forbes 30 under 30 or Steve Jobs first appearing on the cover of TIME at 26. In these fast-moving industries, success is not something that you arrive at or over the course of a long career, but it’s rather something that happens as a consequence of a lucky combination of good timing, market vision, and long periods of work with enormous hours. So our paradigm about what success looks like starts to change in that period.

And then in the 90s, you’ve got a growing proportion of the economy that is devoted to services rather than manufacturing or agriculture, which is a world in which the old limits around working hours no longer really apply. There’s no factory whistle any longer, and you don’t come in from the field when the sun starts to go down. So more and more of us are working in environments in which there are no natural or obvious external limits to how long we can work. At the same time, there’s a growing insecurity across all kinds of professions. Not just in manufacturing as it was in the 70s and 80s, but also in white-collar labor. And in that world, not only are there no natural limits to working hours, but overwork becomes a defensive posture. It’s a way of demonstrating your passion for your work, your loyalty to the organization, and your indispensability.

Productivity is extremely difficult to measure in knowledge work and services. So for a lot of managers and companies, hours of work become a proxy for productivity and output, even though 100 years’ worth of research tells us that, in fact, productivity starts declining after roughly about 40 or 45 hours of labor per week. So people who are working 60 or 70 hours are actually less productive and, very often, are producing less in absolute terms than people who are working 40 hours per week.

The rise of the web and mobile technologies make it possible for us to carry our offices around in our pockets and erase whatever remaining lines there were between work and non-work. Because these devices are always on and always available, we must also be always on and always available. So work has gone from something that happened in discrete periods to a fine powder that’s now blown across all of our days. And, consequently, we live in a world in which a ridiculous number of us check our email within a few minutes of waking up.

Finally, we overwork because our bosses did, because our friends do. Because it seems cool when you’re young and it marks you out as an early achiever, and presumably it gives you access to resources, rewards, promotions, etc. that you wouldn’t have otherwise. So the problem is that there are so many different things that contribute to the sense of overwork being simply part of life, and that makes it harder to envision a different way of working — and put it into practice.

Microsoft’s 2023 Work Trend Index focused heavily on “digital debt,” the phenomenon that we now have more emails, calls, and notifications than we’re humanly able to process. But way back in 2011, you spent a Microsoft-sponsored fellowship researching something called “contemplative computing.” Can you explain what that is?

So the big idea there is that we can create ways of using our digital worlds that help us be more focused and mindful, rather than existing in a state of continuous distraction. The challenge we face is that we live in a world that has plenty of cool, flashy, blinking things which can be very appealing to the lizard parts of our brain, developed by companies who are working very hard to find ways to capture and commodify and resell our attention. So every time we go on Facebook or X [formerly called Twitter] or go through gaming platforms, we’re actually going into hand-to-hand combat with 100 behavioral scientists from Stanford who studied with BJ Fogg and who are A/B testing ways of keeping us online for just a few seconds longer.

The idea behind contemplative computing is that we do not have to surrender to all of these forces that are trying to capture our attention. If we are thoughtful about it, we can redesign our relationships with these devices and tweak their settings and how we use them so they help protect our attention rather than spend it.

A simple example is creating a white list for your phone. Phones are a little bit like toddlers—every call that comes in is equally important. One of the things about little kids is that all things are equally interesting to them: the house is burning down and my shoes are sparkly. Both of those things seem cool. They don’t have terribly good boundaries; they tend to interrupt a lot. And if you don’t give them immediate attention, the world comes to an end. In their default state, our digital devices behave like toddlers. A telemarketing call and a call from a loved one are the same thing. They are insistent about demanding our attention and not very good with boundaries. But there are things that we can do to turn them from four-year-olds into something more like thoughtful personal assistants. And one of them is to construct a white list around who actually has permission to interrupt you.

I think of this as the “Zombie Apocalypse Test.” During the zombie apocalypse, who do you need to call? For those people—there are probably five of them for me—I give them one ringtone, which is the opening bars of Derek and the Dominos’ “Layla.” I will recognize it anywhere. No matter what I’m doing, it cuts through. And the reason I do that is because if my kids call I want to know, and odds are I’m going to respond to them. Everybody else gets the opening bars of one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s solo pieces for cello, which I can hear and then ignore if I’m doing something that’s more important.

The other part of contemplative computing is recognizing that humans have very powerful relationships with technologies and an amazing capacity to use them to extend our cognitive and physical abilities. What’s new is that smart devices don’t just follow our orders, but instead are platforms where other people can insert their own agendas. It’s like driving a car, but the manufacturer of the car wants you to stop at the restaurant that it has a promotional deal with, and the navigation system keeps telling you, “This coffee chain has a deal on mocha lattes.” So the challenge is to recognize that these relationships with our technologies can be really deep and valuable and satisfying, but we need to figure out how to retake control of them in order to get those good things, and not simply for them to define our lives.

“Shortening the workweek creates more time for leisure.”

Have you seen any recent corporate interest in contemplative computing?

The struggle continues. There’s a recognition that it is possible to design things in ways that can help users be more focused. There are lots of popular programs that now offer focus modes—Microsoft Word introduced this a few years ago. Other firms have introduced services or apps that help advance a restful agenda. The meditation app Calm is one nice example of a company that’s actually built to encourage focus and downtime. The problem is, there are enormous amounts of money to be made distracting people, capturing and commodifying their attention, even though doing that by making them feel inadequate or bad about themselves. It’s difficult for an entire industry to abandon a strategy that generated titanic amounts of wealth along with great harm.

You also advocate for the 4-day workweek. What makes you think shortening the work week will allow workers more rest?

First, shortening the workweek creates more time for leisure. Further, the things that companies do in order to make a 4-day workweek a success often involve building better boundaries between work time and non-work time, so that people don’t end up having to carry work home with them and have systems that allow them to actually disconnect from work after hours.

Four-day-week companies also recognize that there is an important social and collective dimension to time pressure, overwork, and burnout. The fact that we all suffer under these regimens—and that we’re all looking for solutions to them—suggests that maybe the problems we face aren’t just because each of us individually is terrible at time management or needs to become a little more efficient. Rather, they’re structural things that we can attack and solve together.

That sounds like it requires an extraordinary amount of organizational skills. It seems difficult to pull off for the millions of smaller businesses that don’t have the resources for such an intense restructuring. Contemplative computing seems pretty easy for everyone to integrate into their everyday lives, but how is it possible to practice the four-day workweek en masse?

First, there is an important collective dimension in contemplative computing: it’s a lot easier to disconnect from your device when everybody else is doing it. So, for example, there are schools that have now implemented rules that say, “No email will be answered after 7 pm.” Creating those kinds of social norms can be really useful in making contemplative computing work.

To speak to the question of the organizational challenges of the four-day workweek: small and medium-sized enterprises that have been the early adopters of the shorter workweek, partly because their decision-making and managerial structures are simpler than big companies’. Small companies that implement the four-day week usually have their original founder or founding team still in charge—sometimes even after 20 years—and they have the moral authority to say, “We’re going to do this radical thing” and bring the rest of the company along with them. The early adopters also are often people who see themselves as experienced outsiders. They have 10 or 15 years’ worth of experience working in their industry and have often worked in leading organizations. They know their sector, have slightly unusual backgrounds and often see themselves as unconventional thinkers. That outsider status makes it a little easier to envision being the first in your industry, or the first in your circle, to do a four-day week.

I think it also appeals to transformational leaders more than it does to transactional leaders. Transformational leaders create the conditions under which their employees can do great work, meaningful work, and have plenty of autonomy. They’re not managers who see themselves as overseeing a system and looking at spreadsheets and charts and making sure that everyone’s hitting their numbers.

The four-day week works across all kinds of industries. We see it not just in creative service firms or small startups, but my most recent projects have been with a hospital chain on the East Coast that did it for their nurse managers, and Colorado’s Golden Police Department. Just like any technology, it starts off as this crazy, cutting-edge thing and then moves into the mainstream, becomes easier to operate, and something that more people can adopt because they’re more familiar with it.

I think the techniques necessary to adopt the four-day week appeal first to early adopters and the people who want an advantage in the marketplace, who see a value in being the first mover, and want to stake a claim to being one of the innovators doing a novel thing that is an expression of their company’s values—whether it’s care for their people, or a desire to make work more sustainable, or be an innovator in process and technology. But it’s something that’s becoming more accessible to a lot of companies, of all sizes, to leaders and workers of all kinds.

The final thing I would say is that the four-day week is very much a collective enterprise, and while it’s useful to have transformational, visionary leaders at the outset, the work is really done by everybody together. And one of the things that we know about the performance of groups is: under challenging circumstances, when you compare a group made of superstars and then everybody else to a group of people who are all pretty good and are committed to their work, that second group is able to outperform the first under virtually all conditions. So you don’t need to be exceptional. You just need to care about your work, get along with your colleagues, and want to make the four-day week a success.

Besides contemplative computing and the four-day week, are there other practices you advocate for that alleviate overwork and mass burnout?

I’m working with an architecture firm right now, and their head of HR described the place as “100 type-A personalities who want to make beautiful things.” And that’s a bunch of people for whom learning how to work less is actually a real challenge. I think that people who are very passionate and get real satisfaction out of the work when it goes well are more prone to overwork and burnout than just about anybody else. It’s hard to tell them to switch off and have them actually do it.

One of the big lessons that I learned when I was writing my book, Rest—which, by the way, is just out in a new edition—is that when you look at the lives of really successful people, like Nobel Prize winners and writers and composers, the ones who have long sustainable careers all share a couple things. One is that they work fewer hours than you would think are necessary in order to do really great work—generally 4 or 5 really concentrated hours a day. But they work very, very steadily, every day. They have daily routines that layer periods of work and rest. They also have really serious, engaging hobbies that take them out of their work, both mentally and sometimes physically. And so these are people who mountain climb, sail, go for very long walks, or garden on a daily basis.

So I think this is the important last piece of the puzzle: part of being able to have good boundaries between work and non-work time is seeing things like serious artistic hobbies or exercise not as a waste of time or unproductive, but as activities that will help you have a longer, more sustainable career. Exactly what those activities are will vary from person to person, but I think if you can find yours, it will go a long way in making it possible for you to practice work in a healthier way for your entire life.

“It’s about seeing rest not just as something that you have to do for yourself, but creating more and better rest time is something that everybody can do or have together.”

Do you think it’s really possible to get everything done that needs to get done and also have time for rest? Many feel life penalizes them for any time they take off. It seems like there’s a to-do debt: when we come back from a nap or a day off or a vacation, there are always expenses that were paid late or deadlines that end up burned.

I love the term “to-do debt.” Okay, so it does require better planning and organization, and a greater degree of ruthlessness and a willingness to say no to things, to recognize what’s really important and commit to those things, and opt out of things that are less important. This is all made easier when you’re doing it with other people versus when you have to figure out how to do it on your own.

For me, one of the things that has been essential both for my life as a writer and as a really valuable strategy for creating more time in the day for rest is: when I’m working on a book, I will get up at 5am to write. I find that in the super early morning, I just have ideas that I don’t seem to have at any other time of day. It’s also the case that if I’m up that early—and I’m absolutely not a morning person—I’m not going to spend that time distracting myself with Twitter threads or Instagram. Also, none of my friends or family are up, not even not even the dog. So I’m guaranteed to be able to work without distraction. That means some of the most important work that I do is finished before breakfast. But in order to do that, the other thing that I have to do is set up that morning the night before, which means that before I close the lid on the laptop, I have a Post-it I write down, usually with like three things that I’ve got to work on the next day. I also use the practice of stopping writing in mid-sentence, which makes it easier the next morning as it’s a lot easier to finish a thought than to confront the existential terror of the blank page. I also will do things like program the coffee maker, choose the clothes I’m going to wear, etc. so that I don’t have to make any decisions before I’m actually at the keyboard writing. I automate my morning as much as possible so that my cognitive energies are spent not deciding what sweatshirt to wear, but rather, “How do we end this sentence?”

I think you also have to recognize that the work of getting out of any debt, whether it’s temporal or financial or something else, is three times harder than the work of maintaining a stable, balanced life or balance sheet. It does require continuous discipline, but once you get there, it’s not as hard to stay there. It is something that’s easier to do at some times in life than others, though. Even if a certain time-intensive work really matters to you, there are seasons of life when other things are more important, and it is okay to pay attention to those things.

What can governments, companies, and individuals do to lessen overwork?

Let’s start small and work up.

At a personal level, I think taking rest seriously and having things in your life that are worth resting for is thing number one. As part of that, it really is valuable to have processes that help you make choices and do your work more effectively. One of the reasons that highly creative people can work 4 or 5 hours a day and produce things like The Origin of Species or the Fifth Symphony is that they are incredibly focused in the time that they are working, and they let nothing distract them. They virtually designed their entire days around part of these periods of deep, focused work. And if you’re able to layer periods of deep work and deliberate rest, it means that you can both get a lot done in those periods and have more time for recovery and leisure throughout the day.

At the social level, I think if this is something that you can do with other people to whatever degree, that’s a great thing. All too often, one person’s rest has been another person’s invisible labor. Some of the people who have been most eloquent about the importance of leisure as an essential ingredient in the good life were slave owners. The cautionary tale there is that it is easy to construct regimes in which my rest becomes someone else’s work. But we also live in an era of tremendous labor-saving technologies that, when deployed properly, can democratize rest and make it possible for all of us to do this better.

It’s about seeing rest not just as something that you have to do for yourself, but creating more and better rest time is something that everybody can do or have together. It’s maybe an awkward initial conversation, but the results can be particularly great at the organizational level. You can do it within your own household, with a spouse, or with kids who are old enough. There are a host of practices around creating more free time that help you give back to your employees in the form of a shorter workweek. There are studies that tell us that the average office worker loses around 2 to 3 hours of productive time every day to overly long meetings, distractions, or work or processes, which means the 4-day week is actually already here for a lot of us. It’s just that we’re coming in on Friday and sitting in meetings and trying to figure out where the toner cartridges are. So if you can get a handle on meetings, on distractions and outline a process, then you can go a long way to making a 4-day week possible. The important thing is to do this collectively so that everybody has an incentive to cooperate when you develop new social norms around meetings and implement other time-saving practices. Everybody should work together so that everyone can leave at the end of the day on Thursday and enjoy a three-day weekend.

Then at the national level, we still have countries that are fighting for a five-day workweek or a 40-hour week. And rather than say what we ought to do at the national level, I think there we’re just entering an age where we are starting to see serious experimentation by governments with incentives to shorten working hours. Two countries, Iceland and the United Arab Emirates, have shortened working hours for the public sector and in the case of the UAE, also for schools. And there are town and state-level governments in the United States, Canada, and Denmark doing smaller-scale experiments that look at how combinations of tax breaks, changes to employment law, and changes in workplace regulation incentivize employers to implement shorter workweeks. Overall, the basic practice of how you do it really isn’t a mystery. It’s just a matter of figuring out at the state level what combination of tools is going to work for your country or for a particular industry.

Photos: Patrick Beaudouin for Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every week!

Inspirez-vous davantage sur : Inspirations pour s'épanouir au travail

From hobby to side hustle: 10 steps to turn your passion into a career in 2025

Have you been waiting for the right moment to turn what you love into a paid gig? 2025 is your time!

18 déc. 2024

Patience, balance, and multitasking: How parenthood shaped my career

Parenthood changes everything—including your career. These working parents share exactly how.

11 déc. 2024

The traits of a great boss (and how they make your work life better)

What makes a great boss? Effective leaders do more than manage tasks—they create a workplace where people feel supported, encouraged, and inspired.

13 nov. 2024

Leading without limits: How to shine as a leader, title or no title

Lab expert Ginny Clarke explores how being a leader isn't just reserved for execs ...

09 avr. 2024

Green influence: Championing sustainability from any desk

Yes, you too can turn your job into a catalyst for change.

07 mars 2024

La newsletter qui fait le taf

Envie de ne louper aucun de nos articles ? Une fois par semaine, des histoires, des jobs et des conseils dans votre boite mail.

Vous êtes à la recherche d’une nouvelle opportunité ?

Plus de 200 000 candidats ont trouvé un emploi sur Welcome to the Jungle.

Explorer les jobs